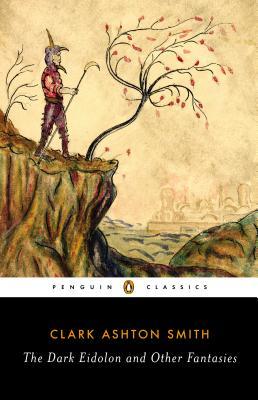

This is part one of what aims to be an overview of the short fiction of Clark Ashton Smith (1893-1961) as found in The Dark Eidolon and Other Fantasies (Penguin, 2014.) Major plot spoilers will be avoided, with only minor plot details and ‘set ups’ revealed along with matters of setting.

Like his contemporaries H.P. Lovecraft, Robert Howard, C.L. Moore and Fritz Leiber, Clark Ashton Smith was a writer of weird fiction and fantasy stories who flourished in the early 20th century while submitting his works to Weird Tales and similar pulp magazines. Now he is closely associated with H.P. Lovecraft, with whom he shared a long correspondence along with ‘Lovecraftian’ preoccupations with oblique malevolent forces, ancient beings, forbidden and dangerous knowledge, and primordial phenomena. CAS can then be enjoyed in this context, of Lovecraftian and weird fiction; but a reading of The Dark Eidolon and Other Fantasies also reveals an author of a more multi-faceted nature, one whose varieties of setting and tone place him as an author of literary relevance outside of the Lovecraft circle. This should be apparent by the following outline of a handful of his short fiction, one which summarises points of narrative, setting, and thematic content for each.

We begin our overview with The Tale Of Satampra Zeiros (1929.) This is weird tale that recalls the aborted theft of an abandoned temple by the narrator and his accomplice. The description of an ancient city overgrown with giant foliage is full of foreboding, while the apparition they encounter in the temple is in the Lovecraftian style. One aspect that distinguishes this story from the norm is the voice of the narrator, of a tone which captures ably the boastful, selfish and conceited nature of a thief:

“I can say without flattering myself, or Tirouv Ompallios either, that we carried to an incomparable success more than one undertaking from which fellow-craftsmen of a much wider renown than ourselves might well have recoiled in dismay. To be more explicit, I refer to the theft of the jewels of Queen Cunambria, which were kept in a room where two-score venomous reptiles wandered at will; and the breaking of the adamantine box of Acromi, in which were all the medallions of an early dynasty of Hyperborean kings. It is true that these medallions were difficult and perilous to dispose of, and that we sold them at a dire sacrifice to the captain of a barbarian vessel from remote Lemuria: but nevertheless, the breaking of that box was a glorious feat, for it had to be done in absolute silence, on account of the proximity of a dozen guards who were all armed with tridents.”

With baroque prose that is evocative of an ancient setting, Clarke deploys a cunning and arrogant anti-hero more like Jack Vance’s Cugel than the academic figure that is the Lovecraftian cliche.

The Last Incantation (1929) is about an old, powerful and feared magician who sits in a tower above a city, wishing to revive a former lover in order to rid his feelings of ennui. At five pages this is a shorter piece of narrow focus, about the problem of knowledge and memory. The necromancer’s appearance, dwelling and art are depicted in a fine detail that further indicative of CAS’s ornate storytelling, this time in the third person mode:

The Last Incantation (1929) is about an old, powerful and feared magician who sits in a tower above a city, wishing to revive a former lover in order to rid his feelings of ennui. At five pages this is a shorter piece of narrow focus, about the problem of knowledge and memory. The necromancer’s appearance, dwelling and art are depicted in a fine detail that further indicative of CAS’s ornate storytelling, this time in the third person mode:

“Now Malygris was old, and all the baleful might of his enchantments, all the dreadful or curious demons under his control, all the fear that he had wrought in the hearts of kings and prelates, were no longer enough to assuage the black ennui of his days. In his chair that was fashioned from the ivory of mastodons, inset with terrible cryptic runes of red tourmalines and azure crystals, he stared moodily through the one lozenge-shaped window of fulvous glass. His white eyebrows were contracted to a single line on the umber parchment of his face, and beneath them his eyes were cold and green as the ice of ancient floes; his beard, half white, half of a black with glaucous gleams, fell nearly to his knees and hid many of the writhing serpentine characters inscribed in woven silver athwart the bosom of his violet robe. About him were scattered all the appurtenances of his art; the skulls of men and monsters; phials filled with black or amber liquids, whose sacrilegious use was known to none but himself; little drums of vulture-skin, and crotali made from the bones and teeth of the cockodrill, used as an accompaniment to certain incantations.”

In a shift of tone and setting is the next story The Devotee Of Evil (1930.) A local novelist, the narrator (and apparent stand-in for CAS) is at a library when he meets a man who has bought a dilapidated house that has been the scene of a grisly murder. By conversation he learns that his new acquaintance is devising a way to manifest pure evil. This is a macabre tale in suburbia that reminds me of Lovecraft’s early-mid period stories, and indeed I learned afterwards The Lurking Fear was a direct influence. It reminds me of The Music Of Erich Zann and Cool Air, where the protagonist meets an increasingly strange man. It’s also a departure from the baroque fantasy stories that have preceded in this collection. The Devotee Of Evil is less ornately told than these, in a stylistic shift that suggests Smith’s versatility. In any case, the passages of cosmic horror are as good as anything from Lovecraft, in this story about the nature of evil and problem of knowledge.

The Uncharted Isle is from 1930. After a shipwreck, a New Zealand sailor is washed onto a Pacific island where he encounters anachronistic phenomena, including beings of an inscrutable and curiously preoccupied ancient race. This is ultimately a tonal piece that contains little action, where the author depicts extensively the sailor’s feelings of disassociation through the first person perspective. It’s also an ambiguous story because it is unclear whether the protagonist’s experiences are imaginary, paranormal, or actual; seawater induced hallucination, time-slip, ghosts, or an isolated species of primordial man.

In The Face By The River (1930) a man comes to terms with the murder of a lover. S.T. Joshi notes that the story is an anomaly with Smith’s work due to its realist treatment of murder. It’s a credit to the author, then, that it is well done piece, a focused depiction of a murderer’s psychology in a contemporary setting. It is bolstered by some asides about the nature of time and the reality-shifting aspect of the murderer’s guilt, asides which would not feel out of place in Borges.

In a return to the fantastic I next read The City Of The Singing Flame (1931), which is as good an account of inter-planetary travel as any. The narrator is a weird fiction author who is hiking in Crater Ridge, California, where he reaches two unusual-looking rocks. When he steps between them, he is transported to another world of an amber sky, violet grass, monolith-lined pathways, and a city of large red stone in the near distance. In an device that is emblematic of weird fiction the story is written in the form of journal entries that are found by a fellow author. Clark depicts an alien world full of unusual beings and phenomena that is evocative of irresistible yet foreboding promise for the narrator, most of all the singing flame which is the seductive centrepiece of the story. There are many Lovecraftian tropes in here, of dangerous knowledge, portals and strange beings, but CAS’s prose is unlike anything from Lovecraft; more visual, exotic, pleasingly rhythmic and felicitous (and more on this final aspect later.)

In a return to the fantastic I next read The City Of The Singing Flame (1931), which is as good an account of inter-planetary travel as any. The narrator is a weird fiction author who is hiking in Crater Ridge, California, where he reaches two unusual-looking rocks. When he steps between them, he is transported to another world of an amber sky, violet grass, monolith-lined pathways, and a city of large red stone in the near distance. In an device that is emblematic of weird fiction the story is written in the form of journal entries that are found by a fellow author. Clark depicts an alien world full of unusual beings and phenomena that is evocative of irresistible yet foreboding promise for the narrator, most of all the singing flame which is the seductive centrepiece of the story. There are many Lovecraftian tropes in here, of dangerous knowledge, portals and strange beings, but CAS’s prose is unlike anything from Lovecraft; more visual, exotic, pleasingly rhythmic and felicitous (and more on this final aspect later.)

This story is followed by The Holiness Of Azadarac by Clark Ashton Smith (1931), a tale of time travel in a secondary world, Averoigne, that is modeled on a region in 12th and 5th century France. At the outset, a renegade Christian bishop plots to intercept a young Benedictine monk who has fled his mansion after obtaining proofs of his pagan practices and demon worship, including that of Iog-Sotot (Yog-Sothoth?) The narrative concerns what happens to this nephew after he is caught and transported seven hundred years back to the same location. This is a tale of the tension between the pagan and Lovecraftian versus Christian morality. It is also of a light and playful tone, as CAS plays with the cliches and archetypal characters of medieval literature; the venial cleric and his henchman, the young and naive monk, and the machinations and heaving charms of a femme fatale sorceress. Overall it’s an entertaining short story that feels like it’s told with a nod and a wink.

If we pull together this handful of stories then an idea of CAS’s versatility should emerge. Here we have seen the expected tropes and ideas that are expected of a pulp and weird fiction author; tales of tomb raiders, time travel, primordial gods, lost civilizations, forbidden knowledge, aliens, portals to other worlds, as well as macabre tales of murder – all very pleasing to those who come to Smith via Lovecraft, as myself. But Smith goes even further and wider by treating his intimations of cosmic horror and the macabre with the kind of exoticism, visual splendour and wry humour that would not be encountered in HPL. I cannot recall the sensuality and temptation of The Singing Flame and The Holiness of Azadarac in Lovecraft or Robert Howard (I have encountered it in C.L. Moore’s Shambleau.) Note also the humour to be found in Satampras Zeiros’s roguish arrogance – by no means the urbane academic protagonist that figures in much Lovecraftian fiction. Even further, witness the breadth of Smith’s settings, which encompass the exotic pre-historical fantastical secondary worlds of Hyperborea and Atlantis, the quasi-historical Averoigne, and the contemporary suburban settings of The Devotee Of Evil and The Face In The River.

And in all things he is felicitous. Smith enjoys deploying an unusual or archaic word or turn of phrase. This might be infuriating in other authors, but after finding the intended meaning the word choice is appreciated. I speculate that this is borne of Smith’s autodidactic education and poetic preoccupation, this ever-awareness of the specific impression of a lesser-used synonym, one that can also produce a more pleasing rhythm of sentence. Sometimes it is better to call a moth-like creature a lepidopter, describe decay as verdigris, or have a prelate be exigent where a bishop could be demanding. Thereby Clark’s writing can be, as well as other qualities, demanding on the reader. Like his progenitors Gene Wolfe and Jack Vance, re-reads and a dictionary can be necessary for a full appreciation of his short stories, but this appreciation reveals satisfying subtleties of visuals, tone, and meaning. This felicity and exacting attitude is how Clark is so capable of producing imaginative stories that deploy the tropes of Lovecraftian fiction, weird fiction and fantasy fiction with a variety of settings, protagonists, tones and structures, first or third person, supernatural or realist, in secondary worlds or contemporary, and being variously wry, elegiac, exotic, sensual or foreboding. This variety distinguishes Clark within his contemporaries as a most chameleonic writer.